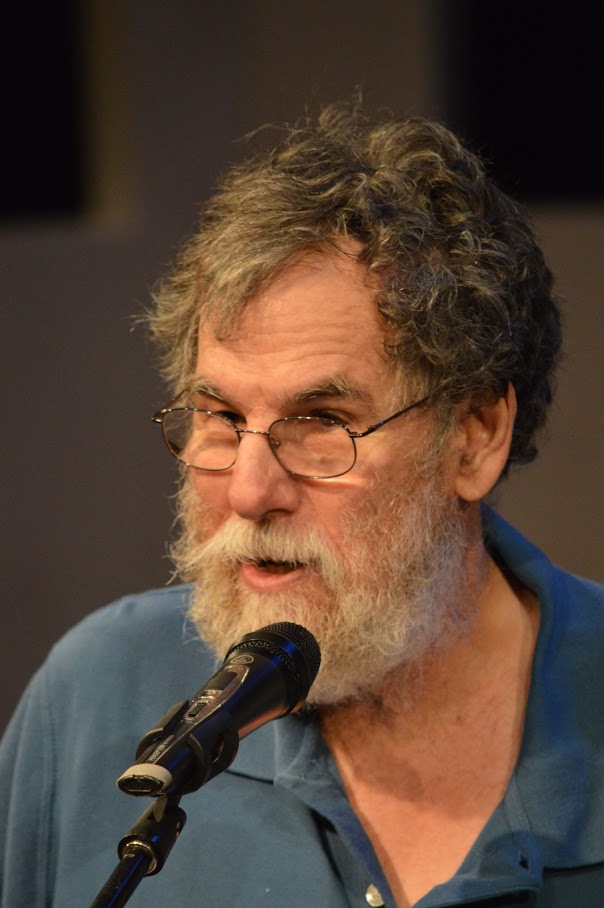

An Interview with Kenneth Weene

My health and my wife’s required a move out of New York to a warmer, drier, and more peaceful life in Arizona; first in Phoenix and now in Tucson. It was in Phoenix that I started to write as my major endeavour.

In conversation with Karunesh Kumar Agarwal, Managing Editor, Pegasus Literary, Kenneth Weene tells us about his success as an international poet. https://www.amazon.com/COURSING-Kenneth-Weene/dp/8182539250

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: Tell us about you and your background.

Kenneth Weene: I grew up in the Northeast of the United States, what is called New England. Much of my identity was forged during the summers when we were in Maine. My parents ran summer camps for children, and those summers were fraught with both the joys of nature and the familial conflict that helped shape both my career choice, a psychologist, and the introspective and often turbulent nature of my poetry.

At 14, it was decided that it would be better for both myself and my family if I were to go to boarding school. That was the same year that my older brother went to college. The family had always focused on him. I wasn’t even “the spare,” but rather an after-thought. I had hoped that I mattered and that his leaving home would give me a moment in the sun or at least my father’s attention. Wrong!

From boarding school I went on to Princeton University; so I guess I’m reasonably bright. After some years of depression and desperation, I went to graduate school. And, ah the best of fortune, I married a wonderful, creative, intelligent, and good-humoured woman, Roz. Without her, I’m sure I would have drowned in the darkness that swirled inside. Instead, I went on to a PhD in psychology and a career as a therapist.

Towards the end of that career, I started writing. I had always wanted to be a writer, but between the internal sturm und drang and the need to earn a good living, that desire had been held on the backburner. At that point we were still living on Long Island in New York and I settled for an occasional opportunity to publish a poem. One of my first attempts was an haiku which won an honourable mention in a Japanese contest. Another high point was reading at Canio’s Books in Sag Harbor. John Steinbeck had always been one of my favourite writers and Canio’s was his favourite hangout. Canio was still alive and still running the store, and I was the last reader he had before selling the shop. What an honour! To make it even better our “adopted” son, who is a videographer, came to record the reading.

My health and my wife’s required a move out of New York to a warmer, drier, and more peaceful life in Arizona; first in Phoenix and now in Tucson. It was in Phoenix that I started to write as my major endeavour. That was in 2002. Since then, I’ve been keyboarding away at a phenomenal rate. Yes, poetry, but also novels, short stories, and even plays. For some reason, I have become known in other countries and most peculiarly in Africa. Since I love the sound of language—especially English—interacting with people who have distinct accents, rhythms, and even vocabularies is a great joy. Thanks to the internet, I can now do that even though I am too old to travel.

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: What inspires you to write poetry?

Kenneth Weene: That is a great question, but one I cannot accurately answer. I often feel that I have no say in the matter, that the voices are speaking through me. If I can go to prose for one moment, one of my novels was in effect dictated to me; it is the culmination of channelling the voice of a long-dead Native American. Oh, I helped with the voices of the characters, but he told the story. Often, my poems, too, reflect voices that speak within me. Are they from muses or from my own madness or perhaps there is no difference between the two.

One thing I do know is that each poem I write is unique. Its meter, rhyme scheme, flow, meaning: all come together in the moment of creation. Of course, when I speak of “the moment,” I really am talking about a process over time. While a few of my poems appear spontaneously and whole, the vast majority are the result of hours and even days of work. It is amazing to me how the search for one word or perhaps the decision to remove one word can take an agonizingly long time.

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: When did you start writing poetry?

Kenneth Weene: Has somebody accused me of poetizing? How precious that would be of me. I swear I have no such affectation but rather I try to write with an ear to language rather than simply a pen. Seriously, from the earliest memories I have of trying to write in primary school I have been striving to catch the musicality of the words that flow around me. I hear the world through the rhythm and tonality of words; I always have. To me, at my best, I am not writing poetry but rather sharing the symphony in my head. Even when writing exam essays in high school I was doing just that. I can remember arguing with one teacher because I referred to a silver moon and he insisted it would be golden. “No, no,” I wanted to shout; “sibilant s moves us forward better than the guttural g.” And, yes, in case you are wondering, I had indeed seen the moon as silver; the words are always right there in my perceptions.

As a result, my fiction often reads as much like poetry as my intended poems. My editor for one of my novellas remarked to me that it was written in iambic pentameter. I looked at him in surprise and said, “Of course, it is. How else could that language have sounded?”

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: What is the measure of success as a poet?

Kenneth Weene: I can only speak for myself not the hypothetical poet. For me, success is in being heard by a reader and being entered into conversation within that person. I know this has happened when somebody asks about a poem, when they write a review of my work, or when they—oh, blessed day—quote my lines to another person. That last means I have reached a conversation.

Do I want more readers? Of course. I can always use the royalties although poetry or even writing fiction seldom provides a real income stream. But, readers, sales and royalties, good as they are, are insufficient if I have not created dialog between myself and somebody else, perhaps somebody with whom I have never interacted other for their sounding my words and hearing their voices respond.

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: Which contemporary poets do you personally believe will be remembered in the coming years and why?

Kenneth Weene: For an older guy like me, the word contemporary seems unduly burdensome. My poets are primarily the ones I grew up with and came to admire when I was young; they are hardly contemporary. Don’t get me wrong, I do read recent work. Some of it is quite outstanding. But, my conversations tend to be with poets now dead, Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Langston Hughes, Angelou, Dylan Thomas, cummings, Pound, Whitman, Dickinson, and the list goes on. Yes, some dead even before my birth. I mean, seriously, even before this list. I still reread, albeit in translation, the ancient Greeks and those wonderful Victorian English voicers of beauty.

Having said all that, I do enjoy some of the current voices as well. Dove, Simic, Merwin, Oliver, and my close personal friend Cynthia Hogue stand out. I also want to give a shoutout to a woman known for her prose, but who for me is truly a poet: Kingsolver. There is also one voice that I have discovered and who is relatively unknown. In fact, she is so outstanding that I may someday be best remembered as discovering Alicia Kimberly (her nom de plume).

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: Fiction or non-fiction? Which is easier?

Kenneth Weene: I have written very little non-fiction, but I have a few essays that are worth the reading. Strangely, some of my best writing may have been the psychological evaluations I wrote many years back. At the time, I was working for a family court clinic, and I wanted to make sure my words were not the dismissive and dehumanizing chatter of diagnoses and factoids. I wanted to help give meaning to the lives of the people passing through the court and who needed society’s best caring rather than bureaucratic fumbling. Yes, that was not easier but perhaps more rewarding than any other writing I’ve done.

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: Your poems are based on your personal experience or other things such as facts?

Kenneth Weene: Both and more. In some cases I have used my fantasies rather than actual events from my life and I’ve certainly fantasized situations that might have been. Then, too, I think all writers appropriate stories they’ve been told by others. However, at a deeper psychodynamic level, I hope that all my writing is both true to my inner experiences and to something that resonates in us all.

I especially hope that the comment I’ve made here is true of Reliquary, the first section of my collection Coursing.

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: What is your greatest fear?

Kenneth Weene: I assume you mean as a writer, but I will start as a human. My greatest personal, inner fear is that life will force me to go on when I no longer want to. I believe that we all have and should have the right to self-exit, to walk away with dignity when the quality of life ends. My greatest fear at this age is that somehow the medical establishment or the politics of religion will take the freedom to end my life away from me now, late in life, when from every medical and logical perspective it seems most precious.

Now, to my greatest fear as a writer and especially as a poet: that I have somehow wasted an opportunity to have made words sing, that I have left out an aria that should have been written, that I have not published that ditty that might help others to connect, that I have not given voice to that lullaby that might give surcease. And, to be honest, that is why each morning I take time to scan like a great antenna listening for the muses, the voices, the inspirations that might just be there for that day.

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: I liked your poem Where monsters wait. When it was written and why.

Kenneth Weene: It was written late 2021 when I was focused on Reliquary. Reliquary is a primarily psychodynamic self-exploration. That collection is a painful place reflecting both autobiographically and religiously based on my relationship with God and with my Jewish heritage. My relationship with my father had always been difficult, and Reliquary reflects the underlying struggle. The first book I published, for which I used a vanity press, was Songs For My Father. I had to get that out of the way because I was so terrified to stand on my own feet as an author; I feared his condemnation. So, I struggled through that anthology and got it published. With that I could call myself an author and face him down. To be fair, he was quite happy with the book giving copies to everyone he could in his care facility. The day I started working on Where monsters wait I had been rereading Songs, asking myself what if anything from it I might want to revisit in Reliquary. Yes, there are a few pieces in both sections of Coursing that go back to that earlier work; Where monsters wait is not one of them, but that reread was what gave it genesis.

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: Do you write mainly romantic poems?

Kenneth Weene: In the sense that romantic implies a centring on nature and emotion I suppose so; however, I primarily think of myself as a beat poet. I tend to hear both a jazz undertone and a spirituality in my verse. I should, to be fair to myself, add that I do on occasion write more formal verse, a sonnet here, an ode there, and possibly a villanelle someplace else.

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: What is your motivation for writing more?

Kenneth Weene: Yes, I do continue to write, these days mostly poetry and plays—the latter co-authored with my Nigerian colleague Umar Adbul. How can I not when there are still songs in my head and music in the world?

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: Your experience of writing COURSING. Please express your feelings.

Kenneth Weene: Wow, what is it like to put together a collection? First, let’s start with Reliquary. While a few of the poems in that section of Coursing preceded the collection, the idea of writing more autobiographical poems started with the six section poem Surplus. At the first summer camp my parents owned in Maine there was a beautiful old farmhouse complete with root cellar and musty attic. They had bought the place right after World War II, and my father had cannily bid on military surplus which at the time was sold in large room-sized lots. The bidders could not see the interiors of the rooms so the winning bidder would in each case end up with a potpourri of valuable commodities, junk, and just plain usable stuff. My father resold some stuff which paid for the process and brought the rest to Maine, where it could be used in the camp or in some cases stored in that attic.

One day I started thinking about that attic room. It was a strange nostalgia based less on trying to reclaim a memory and more on a psychoanalytic curiosity about the specific memories that came up and associating to them to find meaning. Having worked on Surplus, I could not resist the next poem which was a visit to the attic of our winter home near Boston. One day, hiding from my mother I found boxes of photographs. The memory of those fading black and white pictures! Boxes in the attic was the result of that revisited memory. Those two poems became the obvious, to me anyway, bookends for the collection.

Listen to the bullfrogs sing, the second part of Coursing, is more about the world that is, the one in which I live now. The title comes from a line in one of the poems, A Pendle Hill Grace. Many years ago my wife and I spent a long weekend at that Quaker retreat. That was when and where I had written that grace. It is one of those poems that connect me to the joys of life and in particular to the happiness my marriage has given me. No, I do not live in a world of lollipops, unicorns and rainbows; there are plenty of struggles and more than enough pain to go around, but if we are going to sing the dolorous songs should we not also sing those that remind us to smile and dance?

Karunesh Kumar Agarwal: Thank you very much.

Kenneth Weene: It has been my pleasure.